THE

FIELDEN TRAIL

SECTION 1

Cornholme via West Whirlaw, Orchan Rocks

and Hartley Royd

The trail starts at Todmorden Town Hall and finishes by the statue of John Fielden in Centre Vale Park, a mere ten minutes walk away. Between these two points however, you have got around 19 miles of hike to tackle, some of it over rough terrain. So gird up your loins and let's get going, to the start of Section 1 of the Fielden Trail at:-

Todmorden Town Hall

Having got off the bus, parked your car, or whatever, pause a moment to admire the magnificent yet petite edifice of Todmorden Town Hall. Designed in 1870 by John Gibson, it is in the classical style with a semicircular northern end, and is also endowed with fine statuary expressing the history of Todmorden on its southern-facing pediment. It cost around 54,000 pounds and was built at the expense of Samuel, John and Joshua Fielden; it was opened by Lord John Manners on 3rd April 1875, along with the unveiling of their father 'Honest John's' statue, which stood on the western side of the Town Hall before setting off on its travels. Prior to 1888 the county boundary ran through the middle of the Town Hall, and this is indicated on the pediment (the river also flows beneath the Town Hall).

Firmly embedded in the ground the Town Hall may be, not so `Honest John' Fielden, with whom we have a distant appointment in Centre Vale Park. So lace up your boots, check your watch and we'll be off. St. Mary's Church, opposite the Town Hall, was probably founded by the Radcliffes between 1400 and 1476. If you can spare the time at this stage, give it a visit. The East Window commemorates Mr. John Fielden J.P. of Dobroyd Castle, whose widow presented oak screens in 1904.

Now turn right through the market place to the Market Hall, opened in 1879,

Its foundation stone laid by the Fieldens.

If it's a market day you will see some of the hurly burly and bustle of this independent little border town, which, as you will soon discover, has a charm and character all of its own which is not always immediately apparent.

When I began the walk, the hardware shop at the front of the Market Hall had a handwritten notice which boasted 'DONKEY STONES ARE IN STOCK'. Here is a piece of social history in one phrase: once, in an age of rows of back to back mill workers' houses and cobbled streets, whitening your doorstep with a donkey stone was obligatory, and heaven help anyone who didn't bother to 'donkey' their front step. They were sent to Coventry by the rest of the street. Who says 'keeping up with the Joneses' is a modern phenomenon?

To the right of the Market Hall is a public convenience, and a large open parking area, on the site of what was formerly streets and rows of

houses. Nearby is the recently constructed Todmorden Health Centre, and beyond it a block of flats, Roomfield House (you may have seen it in an episode of 'Juliet Bravo' which is filmed around here). Nearby stood:-

Roomfield School

This was the first Board School in Todmorden, opened in 1878. (The remains of the playground walls can still be seen around the flats.) The Fielden Trail does not visit Roomfield House (there is nothing to see) but instead crosses the little footbridge over the river behind the Market Hall. Pause on the bridge a moment and listen to the following harrowing tale from the statement of Henrietta Shepherd to her son Levi, concerning the brave deed for which her husband James Shepherd was awarded a testimonial and a silver medal from the Royal Humane Society:

"On the 14th August 1891 there was a terrible flood. The River Calder was in full spate, and [downstream of Todmorden] was running level with the canal, forming huge lakes across the valley. Here, at Roomfield, the school was flooded and children had to be rescued from the school. To do this, long planks were put across weft boxes to form a bridge, for the children to cross over. Whilst the children were walking on these planks, one little boy, Samuel S. Fielden, fell into the roaring river and was quickly washed out of sight.

At Springside [about 21/2 miles downstream] people had been alerted about the accident, and were watching the river for a sight of the boy. One of these people, James Shepherd, Foreman Dyer at Moss Bros. Springside, saw the boy in the river and immediately jumped into the river, and reached the boy. Being a powerful swimmer, he managed to get the boy to the side of the river near Callis. Here help was at hand to pull them out. The boy was badly bruised by his rough journey down the river, and only survived a few hours. James Shepherd was none the worse for his ordeal. The courage of this man must be appreciated, when you realise that he had a wife and seven children at home. The youngest, twins, were just two months old.

Later James Shepherd was presented with his testimonial and silver medal. On the face of the medal is engraved:

'Presented to Mr. James Shepherd.'

On the reverse:- 'For saving Samuel S. Fielden from the River Calder, 14th August 1891. Presented with a testimonial from the Royal Humane Society for his bravery.'

The Fielden family also presented him with a new suit of clothes for the one ruined in the river. In one of the pockets was a gold sovereign."

So, as you stare at this babbling little brook and try to envisage what kind of a flood it must have been that could sweep a little boy to his death, cross the footbridge (it has steel rails in a trellis pattern, and crosses the river behind the Market Hall, just below the meeting of the Calder with its Walsden tributary), pass behind the Bus Station, (the river flows between concrete walls here and the buses turn on the far side), and go under the railway viaduct, which carries the railway at a high level over the rooftops of Todmorden. Todmorden Viaduct carries the Manchester line over nine arches, seven of them with a sixty foot span, 541/2 feet above the road. The railway was opened on March 1st 1841, and Thomas Fielden, who was one of the railway company directors, proved to be a thorn in the flesh of the board's chairman on more than one occasion, as we shall see.

Beyond the viaduct, cross waste ground by a garage to emerge by a fish and chip shop. Here turn right down Stansfield Road. High on the hillside to the right can be seen the tower of Cross Stone Church, which has Bronte associations. It was originally built centuries ago to cater for the needs of upland farmers, being rebuilt in 1714, pulled down, and re-erected in 1835. It is presently in a ruinous condition. The Bronte sisters stayed at Cross Stone Vicarage in September 1829.

Now continue onwards, bearing gradually to the left. Soon Stansfield Road joins Wellington Road, coming up from the left. Turn right and pass across a footbridge over the railway, passing a YEB installation on the left to emerge on Stansfield Hall Road near its junction with Woodlands Avenue. Bear right and soon a small road appears on the left, by a ginnel with steps, signed 'To The Hollins', close by the entrance gates to:-

Stansfield Hall

The Fielden Trail bears left up the hill towards 'The Hollins', but before continuing onwards, follow the road on to the right for a short distance, in order to get a peek at Stansfield Hall, a fine mansion by John Gibson. The older building at the far side is the original Stansfield Hall, which in its turn was built on the site of a still older house. 'Honest John's' three sons each built mansions for themselves around Todmorden, and Stansfield Hall was the residence of the youngest son, Joshua Fielden, who was born in 1827.

Joshua became M.P. for the Eastern West Riding, and, like his uncle Thomas, was a director on the board of the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway. He married Ellen Brocklehurst of Macclesfield at Prestbury Church, Macclesfield on 14th May 1851, and besides Stansfield Hall he also owned Nutfield Priory in Surrey, which, according to Mrs. Crabtree, my local informant who has actually been there, is not unlike the house which you see here. In 1869 a railway station was opened nearby; this was because the junction at Todmorden faced towards Manchester and was awkward for through traffic to and from Yorkshire. The Stansfield Hall Station was constructed to remedy this fault and enable Yorkshire trains to serve Todmorden. No trace of it remains today. Of course the original residents of Stansfield Hall were the Stansfields, who we will shortly encounter, although at a much earlier period in time.

From the gates of Stansfield Hall, bear left up the road past The Hollins. This passes The Hollins (below crags) and also Willow Bank. Beyond a row of red brick houses the road narrows into a path for a few yards then widens out again, passing stone houses on the left to emerge at Hole Bottom Road. Ahead lies an old mill chimney (the remains of Hole Bottom Mill). Where the track forks take the left hand route to Holly House, beyond which the track continues onwards to Hough Stones. At Hough Stones the Fielden Trail continues straight on, following a path under hawthorns with a stream on the left. Soon the path bears right, ascending the hillside behind Hough Stones to enter Scrapers Lane, to the left of Wickenberry Clough. Turn left and follow the Calderdale Way. At Scrapers Gate the track bears left and continues straight on between walls. On the left is East Whirlaw Farm and on the right Whirlaw Stones, towering ominously above Todmorden, dominating the skyline. Soon a ruin (West Whirlaw) appears on the left and beyond the gate the route becomes a paved 'causey' over moorland, contouring the hillside among boulders and cotton grass.

By the ruins of West Whirlaw is a good spot to break out the flask and sandwiches and reflect awhile. We have now entered a different world. The urban world that crowded us in the centre of Todmorden is suddenly a vain illusion. HERE is the real world. In Todmorden the moors seem distant; here the reverse is true. If the day be clear there are magnificent sweeping views over the moors and vast open tracts of wild country, dwarfing the urban smoke and clamour below. Stoodley Pike Monument is prominent, and on the far side of the Calder Valley above Todmorden, Mankinholes can be seen, nestling in its hollow below the moors. More to the right in the direction of Burnley,

Todmorden Edge can be seen as a cluster of houses hugging the opposite hillside as if wearing a woolly overcoat against the bleak winter weather. Below in the valley is Todmorden, where the start of the walk can be clearly seen.

If the world below us is modern, then the world above us dwells at the opposite pole. Whirlaw is an ancient prehistoric burial ground, and the strange contorted rocks of the Bridestones, weird and mysterious in mist, are an obvious pagan site. Indeed they offer the appearance of a natural Stonehenge. No ancient man could visit such a place as this without being inspired to awe and worship. The ancient aura seems to linger in the name 'Scrapers Lane', which also suggests to me, like the placename 'Flints' at Crow Hill Sowerby, that ancient artefacts have been found here in more recent times.

Stansfield Hall, former residence of Joshua Fielden MP.

As you pack your flask and continue onwards over open moor, the feeling of close proximity to the past becomes more intense. The landscape has changed, and has become more austere, more primitive. Todmorden, like most mill towns in the Upper Calder Valley, appears like a distant oasis of bustle and worldly activity far below. In winter it is flood prone, yet relatively sheltered, and in summer it appears green and lush. Yet up here, on the upland shelf between the valley floor and the high moors, the real nature of the landscape becomes instantly apparent.

Here time has stood still. The prehistoric worshippers, the legions of Rome, they all departed long ago. In their wake came English, Norsemen and Danes, the first hill farmers, clearing the land, claiming rough pastures from the inhospitable hills, felling the ancient birch forests, digging peat, building farmsteads and laithes, keeping livestock, and, perhaps most significantly of all, carding, spinning and weaving woollen cloth. No doubt there were ancestors of the Fieldens among these people, not to mention the Stansfields, Greenwoods, Radcliffes and various other ancient families indigenous to the Upper Calder Valley.

In the wake of the farmers (and in some cases before them) came the arteries of communication, the drove roads and packhorse ways; and, walking on the old causey stones below the Bridestones and Whirlaw, we might, in this quiet solitude, almost hear the jingle of packhorse bells. 'Long Causeways', ancient boundary stones and wayside crosses all abound in this area. Are they Tudor, Mediaeval, or Viking? Perhaps even older? No one knows. English history went its schoolbook way: red rose fought white, the monasteries were dissolved, first the Renaissance and then the Reformation swept Europe; yet right here, in these bleak northern uplands, we might still be in ancient times, such is the scarcity of information relating to this area as it was in those far off days.

High above the valley floor on this upland shelf, what civilisation there was in the Upper Calder Valley first developed. (The valleys were marshy and thickly wooded.) From this level, with the advent of the Industrial Revolution in the late 18th century, the pattern of development was to move downhill, building factories and towns, leaving solitude and desolation in its wake as the surge towards progress, industry and improved communications led embryonic industrialists like the Fieldens to abandon the stony places of their youth, and become dwellers in, and builders of, large industrial townships like Todmorden.

Up here, in the shadow of rock outcrops and moors, is where the Fieldens (and many families like them) began, eking out a harsh living from bleak upland pastures. Down in the valley is where they went to make their fortunes, and back to the countryside (in gentler climes) is where they returned afterwards to build their great houses, returning not as poor yeoman farmers, but as influential landowners, weighted with honours and privileges.

Walking amongst rough hewn ruins on bleak hillsides we are now at the beginning of our trail of inheritance. Through these upland Pastures (and very likely along this ancient packhorse way) sometime in the middle of the 16th century came Nicholas Fielden, yeoman farmer of Inchfield in the Parish of Rochdale. His father, William Fielden, was also a farmer, though his roots are rather less clear, it heing uncertain as to whether he came from Leventhorpe near Bradford, or Heyhouses near Sabden.

Whatever his roots, however, the business that brought Nicholas Fielden so far from his own home in the adjacent Walsden Valley to these bleak Whirlaw uplands is quite clear: he came as a suitor. On this side of the Calder Valley dwelt Christobel, daughter of John Stansfield of Stansfield, and Nicholas eventually married her. Whether or not Nicholas and Christobel walked hand in hand along these hillsides, the wind in their hair, or were merely the unwilling victims of their parents' dynastic ambitions, we can only speculate. One thing we do know is that their marriage, arranged or not, was fruitful, and we must Hope that they were happy together.

As a result of this union, the farms of Hartley Royd and Mercerfield (which we are shortly to visit) passed to Nicholas' children, of which he had five (four sons and a daughter), before Christobel died sometime after 1582. Nicholas remarried, taking as his second wife Elizabeth Greenwood, who, in 1638 was described as 'living at Inchfield aged' (Nicholas having died in 1626). Whether or not Nicholas' children acquired these Calderdale estates as a result of their mother's inheritance or marriage settlement is uncertain, but it seems likely, as there would appear to be no record of any Fieldens living on this side of the valley prior to this period, which suggests that the lands originally belonged to the Stansfields.

Unfortunately the picture of the Fieldens in the 16th and early 17th centuries is not as straightforward as this. The Fieldens of Inchfield (and later Shore, Hartley Royd and Mercerfield) were not the only family of that name living in the vicinity of what was eventually to become Todmorden. On the opposite side of the Walsden Valley to Inchfield, at Bottomley, another family of Fieldens was firmly cstablished. Whether or not they were cousins to Nicholas' family is not clear. One thing is certain however: in the near future a Fielden was going to marry another Fielden and from this union was to spring that branch of the Fielden family with which this book is concerned.

From West Whirlaw the causey passes over the moor amongst boulders and heather, beneath Whirlaw and the Bridestones, which dominate the horizon on the right. After a succession of metal gates the path becomes a 'green lane' running between walls. Continue to the next iron gate, just beyond which the Calderdale Way branches off to the left, down to Rake Hey Farm and Todmorden. Ignore this route, instead continuing onwards along Stoney Lane, passing trees and ruined farm buildings (named 'Springs' on the 1844 map). Keep going and soon, after a gentle rise, the lane reaches a junction of paths at Pole Gates.

Here a choice must be made. Do not follow the lane onwards, but pass through the gate to the left. From here an indistinct path bears to the right over Hudson Moor to Hudson Bridge and Hartley Royd. Most walkers, however, will be tempted to follow the farm track down to Orchan Rocks. After all, you will argue, I've talked at length about strange rocks and pagan rituals, but I haven't taken my route to any of them! Well now's your chance: Orchan Rocks are not very far off route, and visiting them is well worth the necessary detour, so, just to make you happy, I'll take my main route that way!

The way is quite obvious. Follow the track downhill and then cut across open moorland until you arrive at the Orchan Rocks. Here is another place to break out the flask and sandwiches. If you can stand the 'airiness' of the situation there are superb views over the gorge below. Many names are carved on the slabs, although I could find no Fieldens among them when I was there. The Fieldens would have known this spot however, and, like us, would no doubt have marvelled at its strangeness.

From Orchan Rocks bear right over Hudson Moor. Soon, near some quarrying remains, a distinct path is met with, and Hartley Royd can be seen on the far side of Hudson Clough. Follow the path to Hudson Bridge, then continue onwards, finally entering the Hartley Royd farm road through an iron gate. Turn left to arrive at....

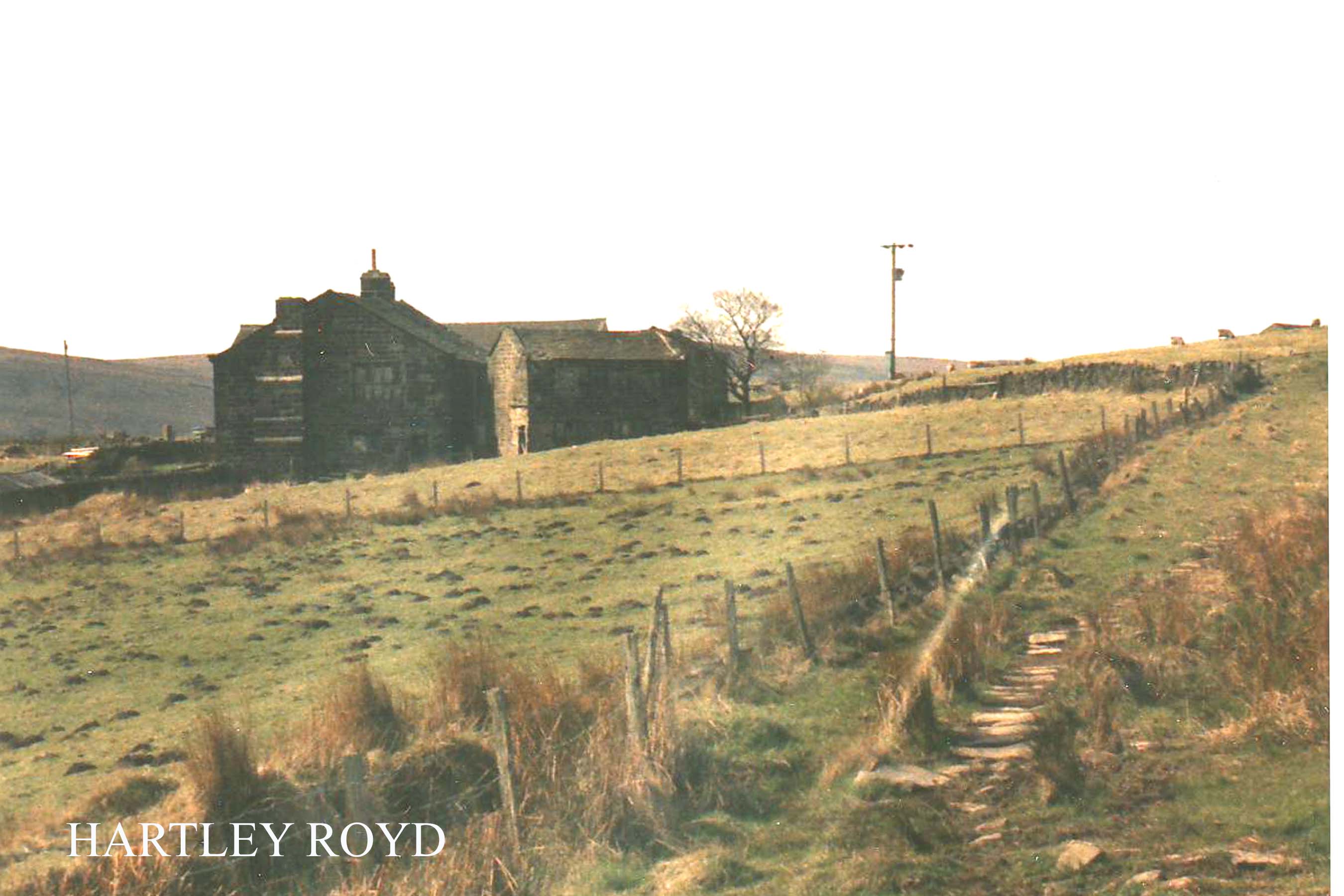

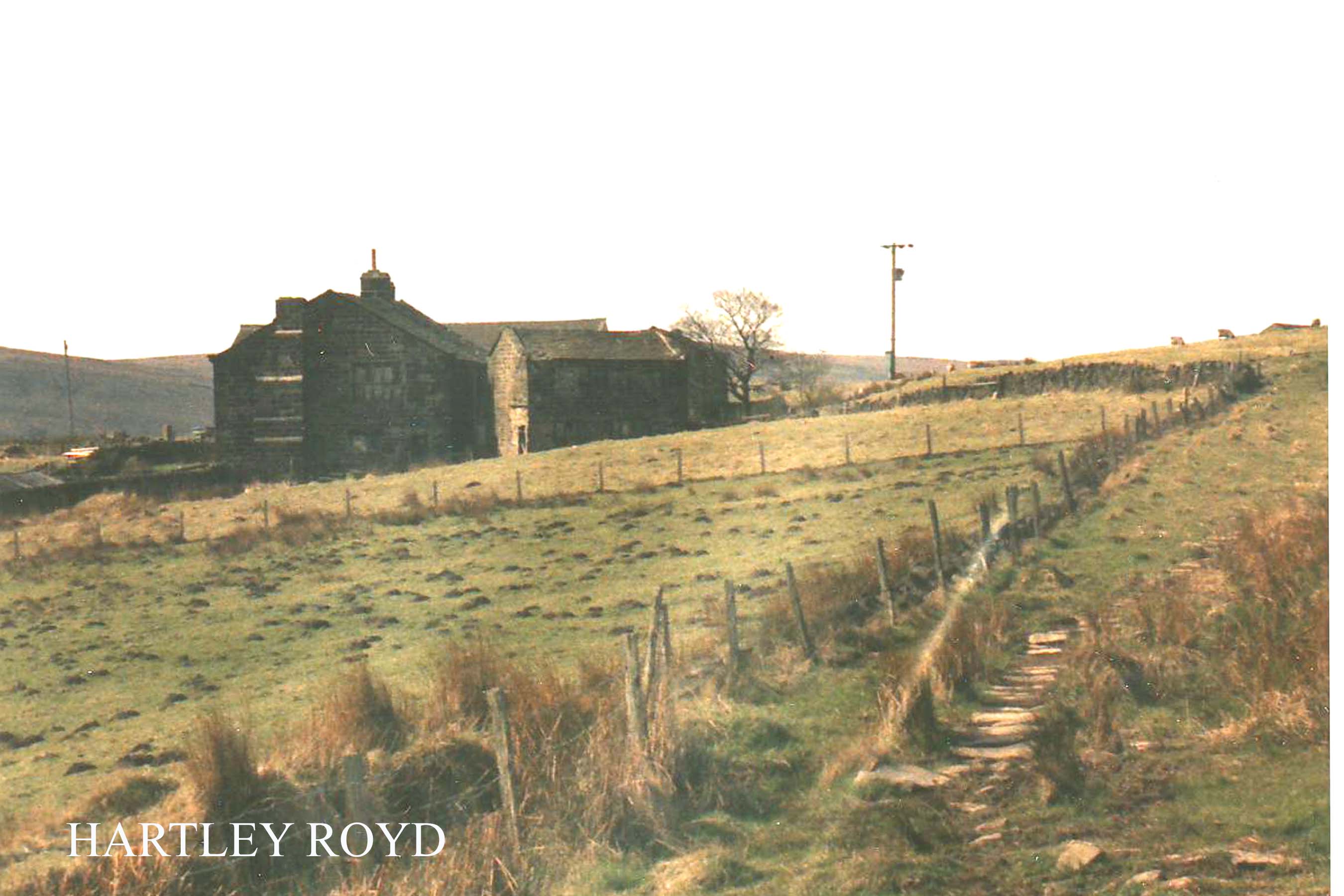

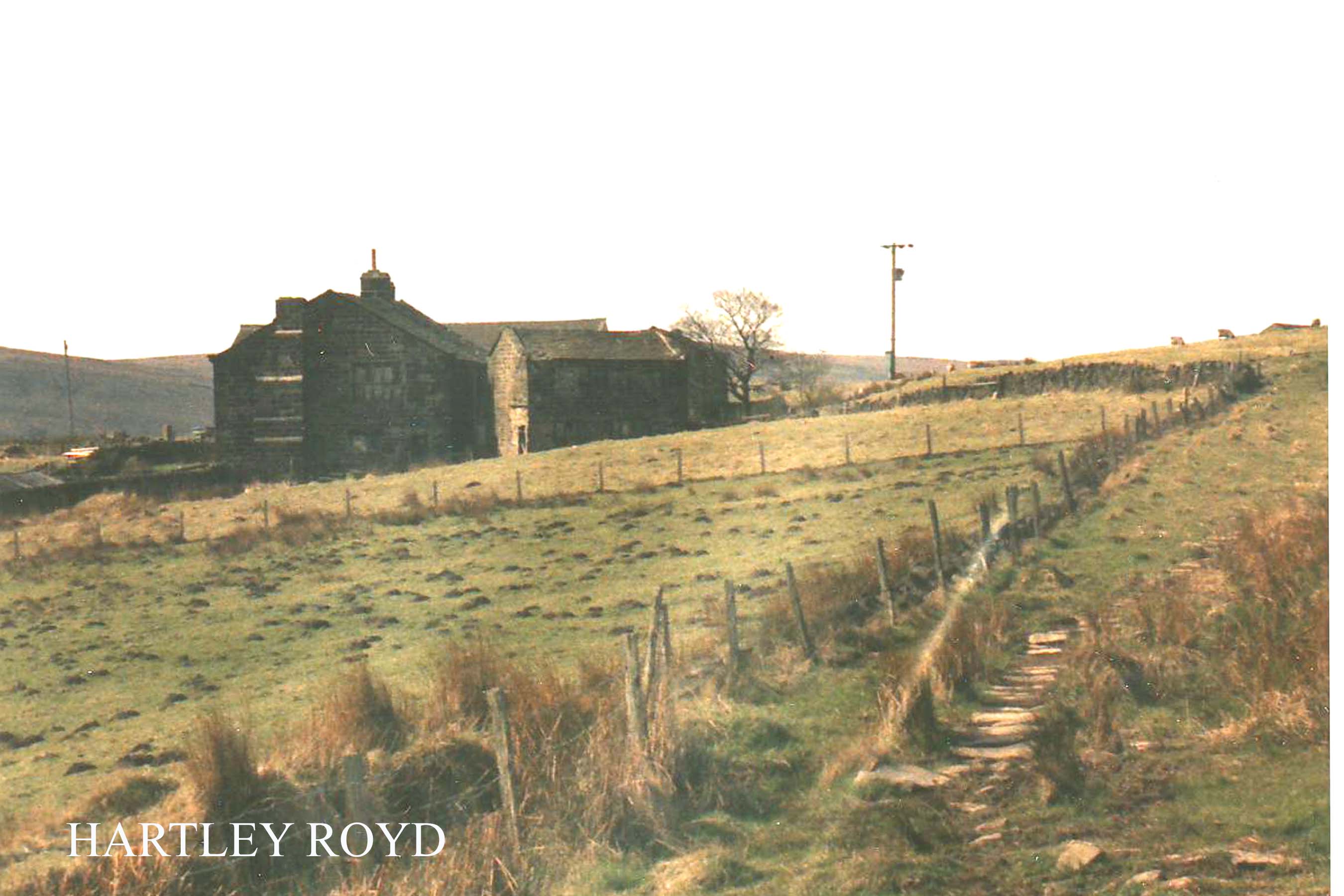

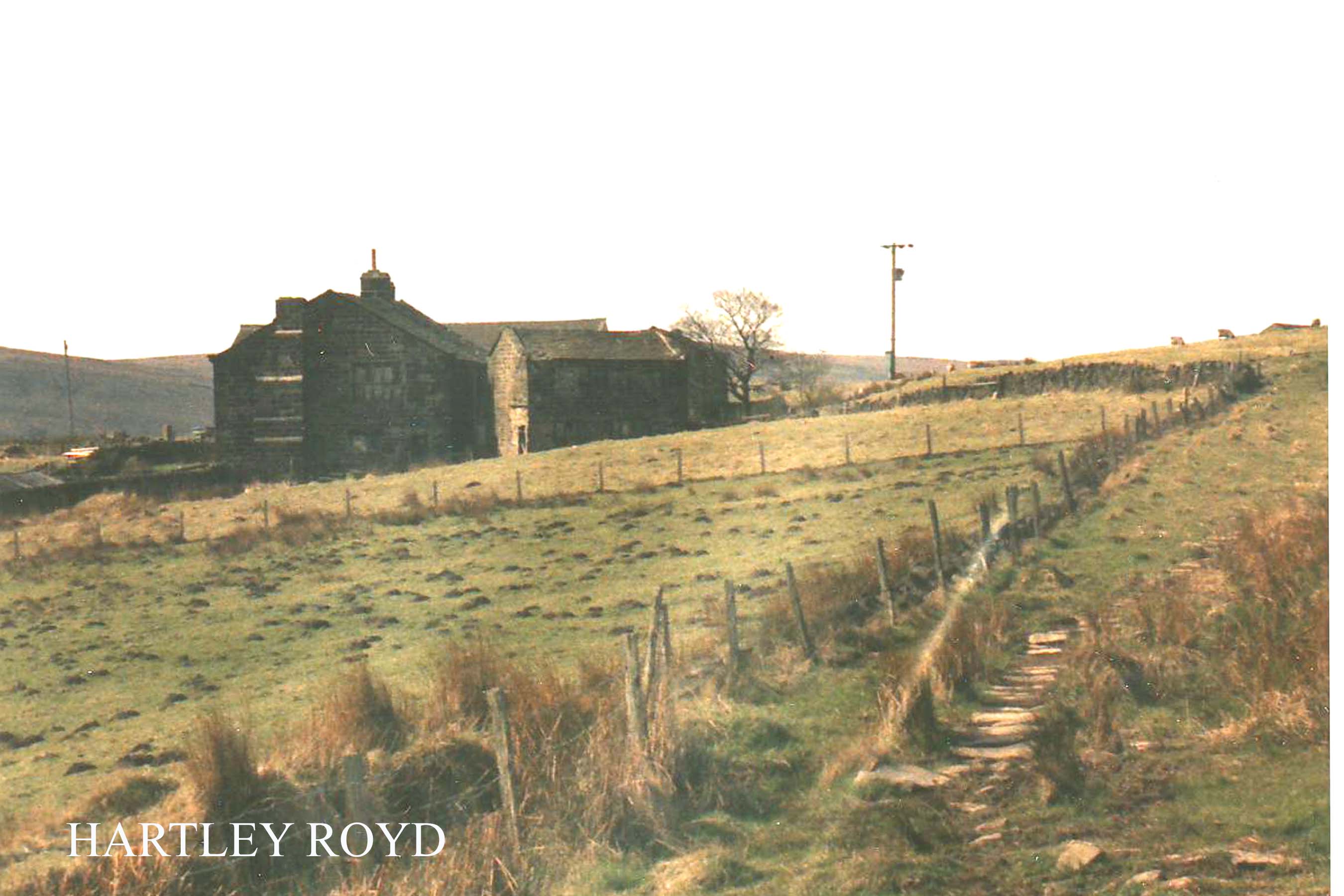

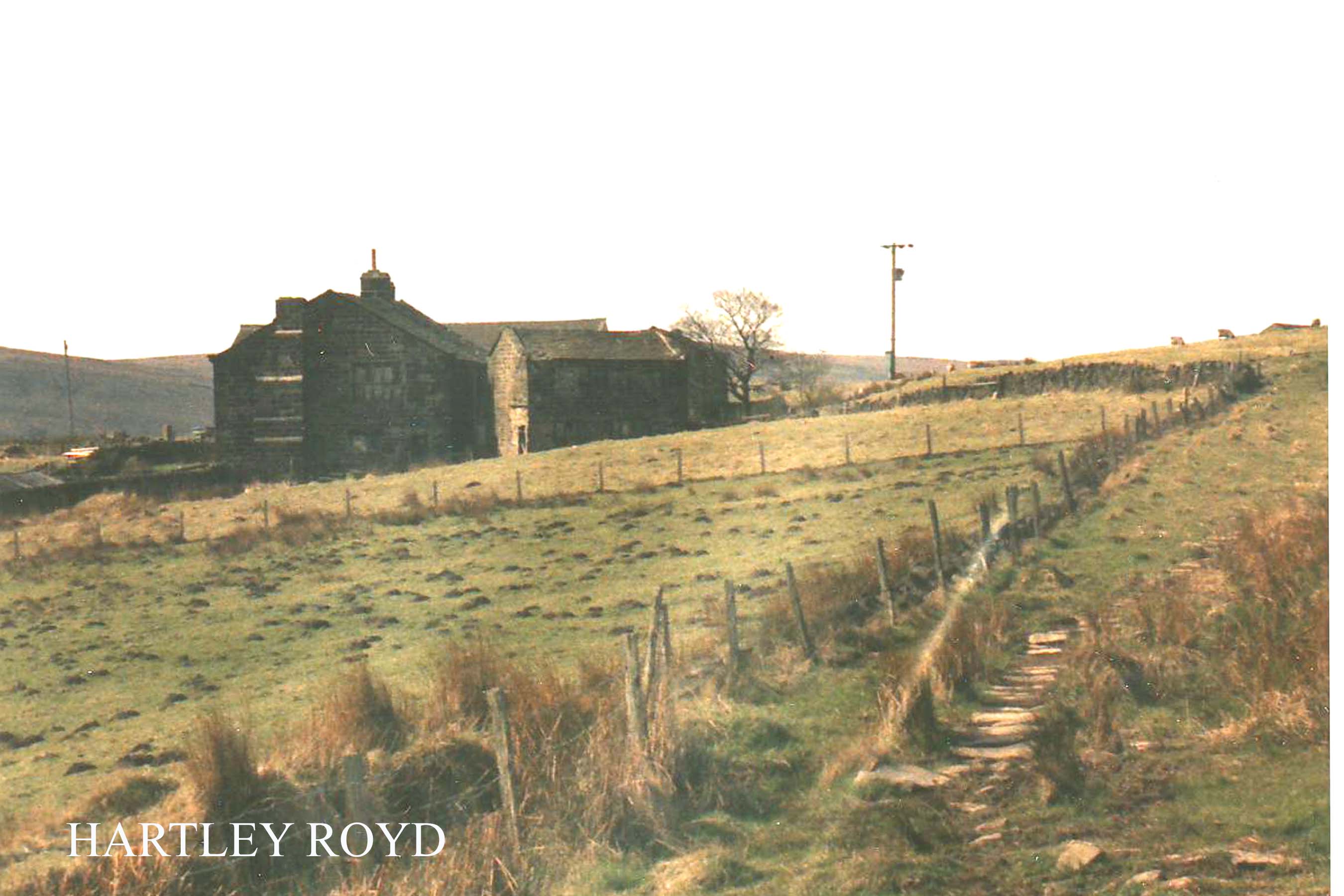

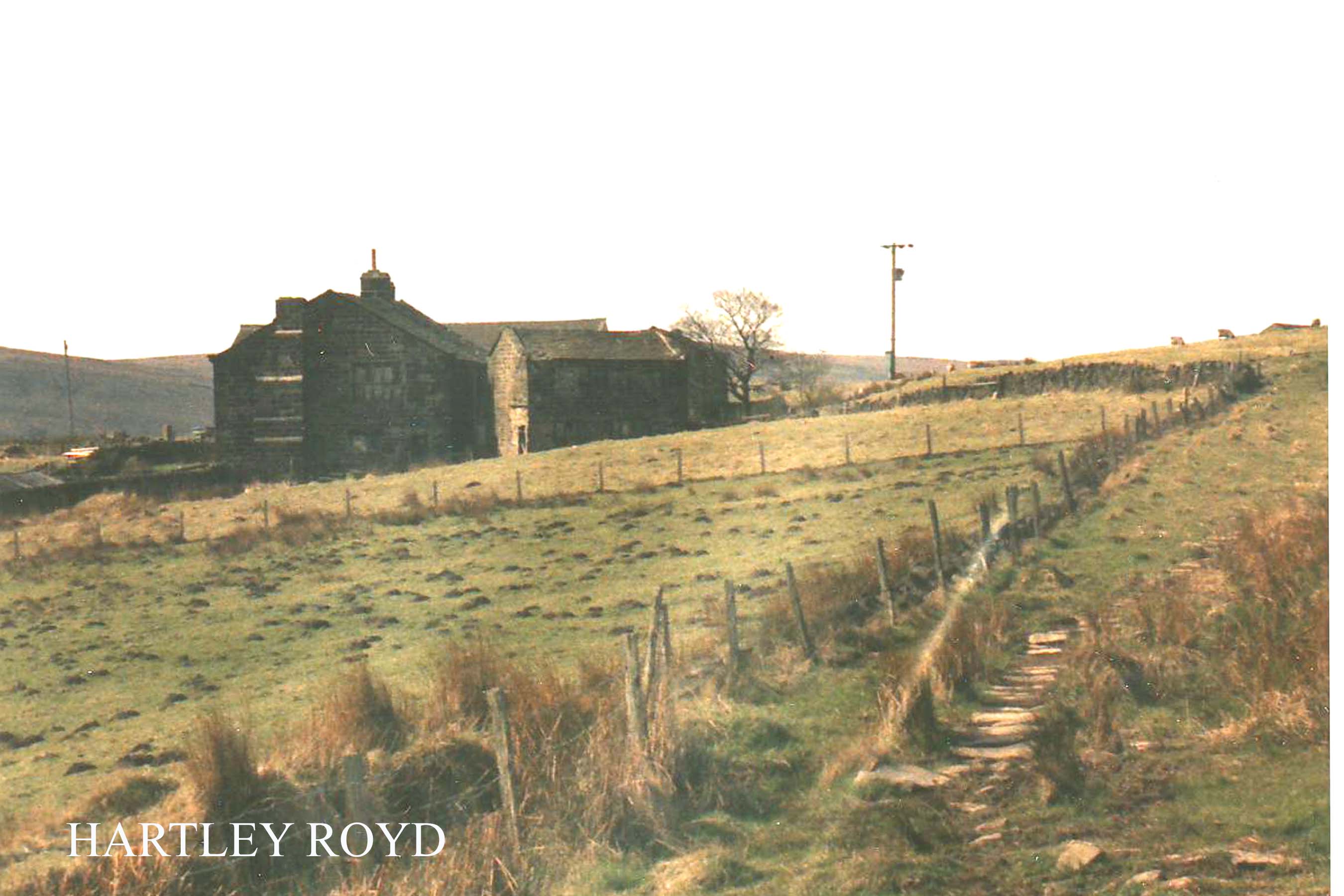

Hartley Royd

In 1624 Nicholas Fielden of Inchfield (whom we have recently encountered) made out his last will and testament, which divided his property amongst his children. To his eldest son John he bequeathed "ffurther Shore" and a moiety (or part) of Mercerfield. Hartley Royd must have been included in this package, for in his own will John Fielden is described as 'John ffeilden of Hartley Royd, Stansfield in the County of York, Yeoman.' The second son, Abraham, inherited Inchfield, and his eldest son, John, also lived at Hartley Royd. Abraham married Elizabeth Fielden of Bottomley, thus uniting two branches of Fieldens, and it is this line whose fortunes we are to follow throughout most of this book. This Abraham Fielden was 'Honest John' Fielden's great, great, great grandfather.

But back to Hartley Royd. Further Shore passed to Nicholas' third son, Joshua, and the other half of Mercerfield went to the youngest, Anthonie. Confused? You soon will be! How, you will ask, does all this relate to the mullioned farmhouse that stands before us? Did John Fielden build the place? The first thing you will notice is the ornate datestone in the north wall, then you will try to read it, but its very serpentine ornateness makes it difficult to decipher. Oh dear, it's in Latin! At this point I was lucky enough to receive the assistance of Mrs. King, the farmer's wife. She said that people often tried to decipher the inscription, so much so that her son had been prompted to sit down one day and find out what it actually did say. It reads as follows...

JOHN FIELDEN AND WIFE ELIZABETH

FROM HARM AT HOME 1724.

Simple eh? No it's not, the date's wrong! The John Fielden we have been talking about died in 1645. This must be a later descendant, and referring to Fishwick's genealogy of the Fieldens only brings more confusion. Our "John ffeilden of Hartley Royd, Yeoman" had a son called John who "inherited his father's lands with the remainder to his son John" (my italics). This second John would have been at least 79 years old in 1724 so it seems likely that it was a third John, the grandson, who carved the datestone and presumably built the present house. I say 'confusing' because the same genealogy also speaks of another "John ffeilden of Hartley Royd", son of Abraham and Elizabeth Fielden. He is named in Elizabeth Fielden's will in 1673, and in accordance with his father's will conveyed Bottomley to his brother Joshua. Has will is dated 14th February 1679!

One possible way of easing this sort of confusion is to realise that these wills are referring to land parcels and not to particular residences. The first John Fielden was "of Hartley Royd", yet he owned "further Shore" and part of Mercerfield. To farm it you did not necessarily have to live on it, and the Fieldens owned patches of land all over the place, houses being divided up amongst relatives, and new pastures being acquired by marriage. Eventually we reach a point where we have to speculate: the John Fielden who was Abraham's eldest son had two sons who inherited lands, Joshua of Swineshead and Nicholas of Shore. Neither of these could have been "from harm at home" at Hartley Royd in 1724, so I am led to conclude that it must have been the third John mentioned earlier who raised the datestone.

Looking at Hartley Royd raises more speculations. If this house was indeed built in 1724, what of the earlier house? The style of the present building with its mullioned windows and externally protruding chimneybreast is more evocative of the 17th than the 18th century. This fact leads us to two possible conclusions. Either the house was built in 1724 in a style which by that time was going out of fashion (this is by no means unlikely as Pennine hill farms were

Hartley Royd from Hudson Bridge.

severely functional in design and styles were a lot slower to change than they were in more 'civilised' areas), or the house was built in the 17th century and underwent alterations in 1724 which resulted in the datestone we now see. And a final question: irrespective of when the present house was built, was there an earlier, perhaps Tudor, house on them site? Or an even older one perhaps? We do not know, we can only speculate.

In 1648 George Fox began public work in Manchester, and William Dewsbury probably preached around Todmorden in 1653. In 1654 John Fielden of Inchfield and Joshua Fielden of Bottomley were reported as being Quakers. By association with his brother Joshua, it is apparent that this John Fielden is the same one who is referred to in th genealogy as being "of Hartley Royd" who "conveyed Bottomley to his brother Joshua". If he lived at Inchfield, his father Abraham did, and John was his eldest son, that should clarify further the mystery of who lived at Hartley Royd.

John suffered for his Quaker faith: in 1665 he was fined for not attending church and as he declined to pay, a cheese was taken off him and sold for 4s. 6d. Three years later he suffered 31 weeks imprisonment for non attendance, whilst the following year five of his oxen were seized and sold (at a value of 23 pounds) and he himself spent eight weeks in jail at Preston. His brother Joshua was buried at Shoebroad on his death in 1693.

John died in 1698, but there is no mention of his resting place. There is another Quaker burial ground at Todmorden Edge, and Mrs King informed me that at Shore there is a field called "t'Quaker Pasture." Quakers were not allowed any monuments or gravestones, so their burial grounds are not immediately apparent. Perhaps somewhere in the "Quaker Pasture" at Shore lie the mortal remains of "John ffeilden of Inchfield and Hartley Royd, Yeoman."

Before visiting Todmorden Edge, and another chapter in the Fielden story, we visit Mercerfield and reflect awhile. From Hartley Royd follow the track that leads through the farmyard towards the valley.

Just beyond the farm buildings another more recent track leads down to a TV booster mast

(leastways that's what I think it is). Just beyond is an iron field gate in a wall. Do not pass

through it, instead hollow the wall to the right. The wall soon becomes a fence running

even more sharply to the right, and Shore Baptist Chapel can be seen on hillside

opposite. At the bottom of the slope a stile enters a dilapidated track coming down from Ridge Gate. Turn left, and

pass through an old gate to the barn at:-

Mercerfield

Only the barn remains, and a rusty old fence straddles the ruins of what once was the house. There is an old door lintel here but the inscription is quite illegible, being badly eroded. The nearest I could get was:

HE C . . . 17 . . .

On the other side of the fence is a more legible stone with the date 1829. Mercerfield was divided between Nicholas and Christobel Fielden's sons John and Anthonie. It seems unlikely that there was a house here in the early 17th century, but there is no way we can be sure. If there was a house here in those far-off days, it must have been a tiny one judging by the ruins of the more recent house.

Here at Mercerfield, tucked snugly on its hillside in a hollow beneath the TV mast, with fine views down the gorge to Cornholme and its mills, is a place to sit down, break out the coffee and let your thoughts wander. Hartley Royd was a fine house, but it was also a farmyard, alive and kicking, fraught with canine menace and bovine sanctity, hardly conducive to flights of fantasy. Here, sitting amongst the pathetic ruins of Mercerfield we are alone with the hills, and we can, beset on all sides with Johns and Joshuas, try to find some clarity in the murky confusion. We can travel in time and try to get a picture of what life must have been like for those yeomen farmers and their families.

What a different world it must have been for those early Fieldens. Nicholas Fielden's grandfather was alive in the reign of Henry VIII. He would have lived through the dissolution of the monasteries, the Pilgrimage of Grace, and would have witnessed some of the repercussions of these events. Life must have been harsh, austere and uncomfortable in those turbulent times. Houses were cold and draughty, and lighting poor or non-existent. The noble 17th century farmsteads and clothier's houses we see on the hillsides today belong to a later generation of housing, born of a minor revolution in techniques of quarrying and stoneworking. Tudor houses in the Pennines were timber framed, often with walls of lath, wattle and daub rather than stone, and smokeholes in the roof rather than sophisticated flues and chimney stacks. Cruck houses, built with skills and techniques passed down from Norse settlers, were common, so backward was this remote upland area. Earthen floors and log fires —these are the kind of houses the Fieldens' mediaeval forebears would have known. The only towns of any note were York, Lancaster and London, and they were far away, almost in another world.

Nicholas Fielden's grandchildren would not have found life too comfortable either. Their homes, though more embattled and sturdy, could have been every bit as uncomfortable. They would keep

livestock on these bleak pastures and supplement a meagre living by producing woollen cloth to be sold at the nearest market, probably Heptonstall. Later, merchants and middlemen would become involved and

the domestic textile industry developed, but at this early stage it would have been every man working for himself.

John and Joshua Fielden, Nicholas' grandchildren, were persecuted for their nonconformist beliefs. They lived through the great Civil War, and were no doubt aware of, if not actually involved with the skirmish "ovver t'hill" at Heptonstall between the Parliamentarian garrison there and Mackworth's Royalists, who marched out of Halifax only to be repulsed by crashing boulders and fast flowing waters. They might also have witnessed the garrison's departure over the moors into Lancashire (perhaps along the very packhorse route that runs above Hartley Royd) and heard reports of the sacking and burning of Heptonstall by the Royalists. Perhaps,

with their Puritan beliefs, they wondered if their familes might next be

ravaged and put to the sword? As Quakers their sympathies would have no doubt lain with the Parliamentary cause, even if their faith forbade them to take up arms.

The only thing we do know is that they survived these turbulent times, probably by minding their own business. Poor hillfarmers like the Fieldens would have little to offer the foraging armies of the Civil Wars. Indeed then, as now, the whole area would have been hostile to people in search of shelter and wholesome food. Good food came from the rich farming areas of the lowlands; the high hills and moors of the Pennines were only good for sheep farming and rough pastures. In the war, food supplies from the arable lowlands would have been cut to virtually a trickle, forcing up prices and bringing privation and hunger to the hillfolk of the Pennines, who eked out a living by selling their cloth. Times must have been hard indeed.

However, the sound of a train coming up the valley towards Cornholme breaks our reverie and we are back to the present day.

Other Fieldens and other centuries await us, so we must say goodbye to

the Fieldens of Shore, and push on up the other side of the valley towards Todmorden Edge. As you descend towards the bottom of the valley, make a good note of the topography of the opposite hillside if you intend continuing beyond Section 1. The path, zigzagging up the hillside opposite to a ruined farm on the edge of the moor, is the way out from the gorge and the first part of Section 2 of the Fielden Trail.

From Mercerfield the route is indistinct and there is a multiplicity of sheep paths. The object is to get down to New Ley, a tiny little farmhouse in a ruinous condition, surrounded by nettles. The roof is starting to collapse now, but its size and interior give a pretty good idea of what Mercerfield must have been like when it was standing. For that reason alone, it is worth stopping for a moment.

From New Ley an enclosed path leads down to another ruined farm with green painted lintels, where it joins a track coming in from the left. The track descends towards a bungalow near some red brick honuses, to emerge into Frieldhurst Road. Turn left and pass under the railways line to emerge into the main Burnley Road.

This is the end of Section 1. If you are not continuing onto Section 2

this is the place to catch a bus back to Todmorden. On foot it is a long walk down a busy road,

but if the hour is late, this is preferable to following Section 2, which involves some

awkward countryside and a lot of ascent, not very enjoyable in bad weather. I'd catch the

bus if I was you, you can always tackle Section 2 on another day when you feel up to it. Don't

worry about it, we'll go on our own!

Copyright Jim Jarratt.

2006 First Published by Smith Settle 1989

Todmorden Town Hall

Having got off the bus, parked your car, or whatever, pause a moment to admire the magnificent yet petite edifice of Todmorden Town Hall. Designed in 1870 by John Gibson, it is in the classical style with a semicircular northern end, and is also endowed with fine statuary expressing the history of Todmorden on its southern-facing pediment. It cost around 54,000 pounds and was built at the expense of Samuel, John and Joshua Fielden; it was opened by Lord John Manners on 3rd April 1875, along with the unveiling of their father 'Honest John's' statue, which stood on the western side of the Town Hall before setting off on its travels. Prior to 1888 the county boundary ran through the middle of the Town Hall, and this is indicated on the pediment (the river also flows beneath the Town Hall).

Firmly embedded in the ground the Town Hall may be, not so `Honest John' Fielden, with whom we have a distant appointment in Centre Vale Park. So lace up your boots, check your watch and we'll be off. St. Mary's Church, opposite the Town Hall, was probably founded by the Radcliffes between 1400 and 1476. If you can spare the time at this stage, give it a visit. The East Window commemorates Mr. John Fielden J.P. of Dobroyd Castle, whose widow presented oak screens in 1904.

Now turn right through the market place to the Market Hall, opened in 1879,

Its foundation stone laid by the Fieldens.

If it's a market day you will see some of the hurly burly and bustle of this independent little border town, which, as you will soon discover, has a charm and character all of its own which is not always immediately apparent.

When I began the walk, the hardware shop at the front of the Market Hall had a handwritten notice which boasted 'DONKEY STONES ARE IN STOCK'. Here is a piece of social history in one phrase: once, in an age of rows of back to back mill workers' houses and cobbled streets, whitening your doorstep with a donkey stone was obligatory, and heaven help anyone who didn't bother to 'donkey' their front step. They were sent to Coventry by the rest of the street. Who says 'keeping up with the Joneses' is a modern phenomenon?

To the right of the Market Hall is a public convenience, and a large open parking area, on the site of what was formerly streets and rows of

houses. Nearby is the recently constructed Todmorden Health Centre, and beyond it a block of flats, Roomfield House (you may have seen it in an episode of 'Juliet Bravo' which is filmed around here). Nearby stood:-

Roomfield School

This was the first Board School in Todmorden, opened in 1878. (The remains of the playground walls can still be seen around the flats.) The Fielden Trail does not visit Roomfield House (there is nothing to see) but instead crosses the little footbridge over the river behind the Market Hall. Pause on the bridge a moment and listen to the following harrowing tale from the statement of Henrietta Shepherd to her son Levi, concerning the brave deed for which her husband James Shepherd was awarded a testimonial and a silver medal from the Royal Humane Society:

"On the 14th August 1891 there was a terrible flood. The River Calder was in full spate, and [downstream of Todmorden] was running level with the canal, forming huge lakes across the valley. Here, at Roomfield, the school was flooded and children had to be rescued from the school. To do this, long planks were put across weft boxes to form a bridge, for the children to cross over. Whilst the children were walking on these planks, one little boy, Samuel S. Fielden, fell into the roaring river and was quickly washed out of sight.

At Springside [about 21/2 miles downstream] people had been alerted about the accident, and were watching the river for a sight of the boy. One of these people, James Shepherd, Foreman Dyer at Moss Bros. Springside, saw the boy in the river and immediately jumped into the river, and reached the boy. Being a powerful swimmer, he managed to get the boy to the side of the river near Callis. Here help was at hand to pull them out. The boy was badly bruised by his rough journey down the river, and only survived a few hours. James Shepherd was none the worse for his ordeal. The courage of this man must be appreciated, when you realise that he had a wife and seven children at home. The youngest, twins, were just two months old.

Later James Shepherd was presented with his testimonial and silver medal. On the face of the medal is engraved:

'Presented to Mr. James Shepherd.'

On the reverse:- 'For saving Samuel S. Fielden from the River Calder, 14th August 1891. Presented with a testimonial from the Royal Humane Society for his bravery.'

The Fielden family also presented him with a new suit of clothes for the one ruined in the river. In one of the pockets was a gold sovereign."

So, as you stare at this babbling little brook and try to envisage what kind of a flood it must have been that could sweep a little boy to his death, cross the footbridge (it has steel rails in a trellis pattern, and crosses the river behind the Market Hall, just below the meeting of the Calder with its Walsden tributary), pass behind the Bus Station, (the river flows between concrete walls here and the buses turn on the far side), and go under the railway viaduct, which carries the railway at a high level over the rooftops of Todmorden. Todmorden Viaduct carries the Manchester line over nine arches, seven of them with a sixty foot span, 541/2 feet above the road. The railway was opened on March 1st 1841, and Thomas Fielden, who was one of the railway company directors, proved to be a thorn in the flesh of the board's chairman on more than one occasion, as we shall see.

Beyond the viaduct, cross waste ground by a garage to emerge by a fish and chip shop. Here turn right down Stansfield Road. High on the hillside to the right can be seen the tower of Cross Stone Church, which has Bronte associations. It was originally built centuries ago to cater for the needs of upland farmers, being rebuilt in 1714, pulled down, and re-erected in 1835. It is presently in a ruinous condition. The Bronte sisters stayed at Cross Stone Vicarage in September 1829.

Now continue onwards, bearing gradually to the left. Soon Stansfield Road joins Wellington Road, coming up from the left. Turn right and pass across a footbridge over the railway, passing a YEB installation on the left to emerge on Stansfield Hall Road near its junction with Woodlands Avenue. Bear right and soon a small road appears on the left, by a ginnel with steps, signed 'To The Hollins', close by the entrance gates to:-

Stansfield Hall

The Fielden Trail bears left up the hill towards 'The Hollins', but before continuing onwards, follow the road on to the right for a short distance, in order to get a peek at Stansfield Hall, a fine mansion by John Gibson. The older building at the far side is the original Stansfield Hall, which in its turn was built on the site of a still older house. 'Honest John's' three sons each built mansions for themselves around Todmorden, and Stansfield Hall was the residence of the youngest son, Joshua Fielden, who was born in 1827.

Joshua became M.P. for the Eastern West Riding, and, like his uncle Thomas, was a director on the board of the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway. He married Ellen Brocklehurst of Macclesfield at Prestbury Church, Macclesfield on 14th May 1851, and besides Stansfield Hall he also owned Nutfield Priory in Surrey, which, according to Mrs. Crabtree, my local informant who has actually been there, is not unlike the house which you see here. In 1869 a railway station was opened nearby; this was because the junction at Todmorden faced towards Manchester and was awkward for through traffic to and from Yorkshire. The Stansfield Hall Station was constructed to remedy this fault and enable Yorkshire trains to serve Todmorden. No trace of it remains today. Of course the original residents of Stansfield Hall were the Stansfields, who we will shortly encounter, although at a much earlier period in time.

From the gates of Stansfield Hall, bear left up the road past The Hollins. This passes The Hollins (below crags) and also Willow Bank. Beyond a row of red brick houses the road narrows into a path for a few yards then widens out again, passing stone houses on the left to emerge at Hole Bottom Road. Ahead lies an old mill chimney (the remains of Hole Bottom Mill). Where the track forks take the left hand route to Holly House, beyond which the track continues onwards to Hough Stones. At Hough Stones the Fielden Trail continues straight on, following a path under hawthorns with a stream on the left. Soon the path bears right, ascending the hillside behind Hough Stones to enter Scrapers Lane, to the left of Wickenberry Clough. Turn left and follow the Calderdale Way. At Scrapers Gate the track bears left and continues straight on between walls. On the left is East Whirlaw Farm and on the right Whirlaw Stones, towering ominously above Todmorden, dominating the skyline. Soon a ruin (West Whirlaw) appears on the left and beyond the gate the route becomes a paved 'causey' over moorland, contouring the hillside among boulders and cotton grass.

By the ruins of West Whirlaw is a good spot to break out the flask and sandwiches and reflect awhile. We have now entered a different world. The urban world that crowded us in the centre of Todmorden is suddenly a vain illusion. HERE is the real world. In Todmorden the moors seem distant; here the reverse is true. If the day be clear there are magnificent sweeping views over the moors and vast open tracts of wild country, dwarfing the urban smoke and clamour below. Stoodley Pike Monument is prominent, and on the far side of the Calder Valley above Todmorden, Mankinholes can be seen, nestling in its hollow below the moors. More to the right in the direction of Burnley,

Todmorden Edge can be seen as a cluster of houses hugging the opposite hillside as if wearing a woolly overcoat against the bleak winter weather. Below in the valley is Todmorden, where the start of the walk can be clearly seen.

If the world below us is modern, then the world above us dwells at the opposite pole. Whirlaw is an ancient prehistoric burial ground, and the strange contorted rocks of the Bridestones, weird and mysterious in mist, are an obvious pagan site. Indeed they offer the appearance of a natural Stonehenge. No ancient man could visit such a place as this without being inspired to awe and worship. The ancient aura seems to linger in the name 'Scrapers Lane', which also suggests to me, like the placename 'Flints' at Crow Hill Sowerby, that ancient artefacts have been found here in more recent times.

Stansfield Hall, former residence of Joshua Fielden MP.

As you pack your flask and continue onwards over open moor, the feeling of close proximity to the past becomes more intense. The landscape has changed, and has become more austere, more primitive. Todmorden, like most mill towns in the Upper Calder Valley, appears like a distant oasis of bustle and worldly activity far below. In winter it is flood prone, yet relatively sheltered, and in summer it appears green and lush. Yet up here, on the upland shelf between the valley floor and the high moors, the real nature of the landscape becomes instantly apparent.

Here time has stood still. The prehistoric worshippers, the legions of Rome, they all departed long ago. In their wake came English, Norsemen and Danes, the first hill farmers, clearing the land, claiming rough pastures from the inhospitable hills, felling the ancient birch forests, digging peat, building farmsteads and laithes, keeping livestock, and, perhaps most significantly of all, carding, spinning and weaving woollen cloth. No doubt there were ancestors of the Fieldens among these people, not to mention the Stansfields, Greenwoods, Radcliffes and various other ancient families indigenous to the Upper Calder Valley.

In the wake of the farmers (and in some cases before them) came the arteries of communication, the drove roads and packhorse ways; and, walking on the old causey stones below the Bridestones and Whirlaw, we might, in this quiet solitude, almost hear the jingle of packhorse bells. 'Long Causeways', ancient boundary stones and wayside crosses all abound in this area. Are they Tudor, Mediaeval, or Viking? Perhaps even older? No one knows. English history went its schoolbook way: red rose fought white, the monasteries were dissolved, first the Renaissance and then the Reformation swept Europe; yet right here, in these bleak northern uplands, we might still be in ancient times, such is the scarcity of information relating to this area as it was in those far off days.

High above the valley floor on this upland shelf, what civilisation there was in the Upper Calder Valley first developed. (The valleys were marshy and thickly wooded.) From this level, with the advent of the Industrial Revolution in the late 18th century, the pattern of development was to move downhill, building factories and towns, leaving solitude and desolation in its wake as the surge towards progress, industry and improved communications led embryonic industrialists like the Fieldens to abandon the stony places of their youth, and become dwellers in, and builders of, large industrial townships like Todmorden.

Up here, in the shadow of rock outcrops and moors, is where the Fieldens (and many families like them) began, eking out a harsh living from bleak upland pastures. Down in the valley is where they went to make their fortunes, and back to the countryside (in gentler climes) is where they returned afterwards to build their great houses, returning not as poor yeoman farmers, but as influential landowners, weighted with honours and privileges.

Walking amongst rough hewn ruins on bleak hillsides we are now at the beginning of our trail of inheritance. Through these upland Pastures (and very likely along this ancient packhorse way) sometime in the middle of the 16th century came Nicholas Fielden, yeoman farmer of Inchfield in the Parish of Rochdale. His father, William Fielden, was also a farmer, though his roots are rather less clear, it heing uncertain as to whether he came from Leventhorpe near Bradford, or Heyhouses near Sabden.

Whatever his roots, however, the business that brought Nicholas Fielden so far from his own home in the adjacent Walsden Valley to these bleak Whirlaw uplands is quite clear: he came as a suitor. On this side of the Calder Valley dwelt Christobel, daughter of John Stansfield of Stansfield, and Nicholas eventually married her. Whether or not Nicholas and Christobel walked hand in hand along these hillsides, the wind in their hair, or were merely the unwilling victims of their parents' dynastic ambitions, we can only speculate. One thing we do know is that their marriage, arranged or not, was fruitful, and we must Hope that they were happy together.

As a result of this union, the farms of Hartley Royd and Mercerfield (which we are shortly to visit) passed to Nicholas' children, of which he had five (four sons and a daughter), before Christobel died sometime after 1582. Nicholas remarried, taking as his second wife Elizabeth Greenwood, who, in 1638 was described as 'living at Inchfield aged' (Nicholas having died in 1626). Whether or not Nicholas' children acquired these Calderdale estates as a result of their mother's inheritance or marriage settlement is uncertain, but it seems likely, as there would appear to be no record of any Fieldens living on this side of the valley prior to this period, which suggests that the lands originally belonged to the Stansfields.

Unfortunately the picture of the Fieldens in the 16th and early 17th centuries is not as straightforward as this. The Fieldens of Inchfield (and later Shore, Hartley Royd and Mercerfield) were not the only family of that name living in the vicinity of what was eventually to become Todmorden. On the opposite side of the Walsden Valley to Inchfield, at Bottomley, another family of Fieldens was firmly cstablished. Whether or not they were cousins to Nicholas' family is not clear. One thing is certain however: in the near future a Fielden was going to marry another Fielden and from this union was to spring that branch of the Fielden family with which this book is concerned.

From West Whirlaw the causey passes over the moor amongst boulders and heather, beneath Whirlaw and the Bridestones, which dominate the horizon on the right. After a succession of metal gates the path becomes a 'green lane' running between walls. Continue to the next iron gate, just beyond which the Calderdale Way branches off to the left, down to Rake Hey Farm and Todmorden. Ignore this route, instead continuing onwards along Stoney Lane, passing trees and ruined farm buildings (named 'Springs' on the 1844 map). Keep going and soon, after a gentle rise, the lane reaches a junction of paths at Pole Gates.

Here a choice must be made. Do not follow the lane onwards, but pass through the gate to the left. From here an indistinct path bears to the right over Hudson Moor to Hudson Bridge and Hartley Royd. Most walkers, however, will be tempted to follow the farm track down to Orchan Rocks. After all, you will argue, I've talked at length about strange rocks and pagan rituals, but I haven't taken my route to any of them! Well now's your chance: Orchan Rocks are not very far off route, and visiting them is well worth the necessary detour, so, just to make you happy, I'll take my main route that way!

The way is quite obvious. Follow the track downhill and then cut across open moorland until you arrive at the Orchan Rocks. Here is another place to break out the flask and sandwiches. If you can stand the 'airiness' of the situation there are superb views over the gorge below. Many names are carved on the slabs, although I could find no Fieldens among them when I was there. The Fieldens would have known this spot however, and, like us, would no doubt have marvelled at its strangeness.

From Orchan Rocks bear right over Hudson Moor. Soon, near some quarrying remains, a distinct path is met with, and Hartley Royd can be seen on the far side of Hudson Clough. Follow the path to Hudson Bridge, then continue onwards, finally entering the Hartley Royd farm road through an iron gate. Turn left to arrive at....

Hartley Royd

In 1624 Nicholas Fielden of Inchfield (whom we have recently encountered) made out his last will and testament, which divided his property amongst his children. To his eldest son John he bequeathed "ffurther Shore" and a moiety (or part) of Mercerfield. Hartley Royd must have been included in this package, for in his own will John Fielden is described as 'John ffeilden of Hartley Royd, Stansfield in the County of York, Yeoman.' The second son, Abraham, inherited Inchfield, and his eldest son, John, also lived at Hartley Royd. Abraham married Elizabeth Fielden of Bottomley, thus uniting two branches of Fieldens, and it is this line whose fortunes we are to follow throughout most of this book. This Abraham Fielden was 'Honest John' Fielden's great, great, great grandfather.

But back to Hartley Royd. Further Shore passed to Nicholas' third son, Joshua, and the other half of Mercerfield went to the youngest, Anthonie. Confused? You soon will be! How, you will ask, does all this relate to the mullioned farmhouse that stands before us? Did John Fielden build the place? The first thing you will notice is the ornate datestone in the north wall, then you will try to read it, but its very serpentine ornateness makes it difficult to decipher. Oh dear, it's in Latin! At this point I was lucky enough to receive the assistance of Mrs. King, the farmer's wife. She said that people often tried to decipher the inscription, so much so that her son had been prompted to sit down one day and find out what it actually did say. It reads as follows...

JOHN FIELDEN AND WIFE ELIZABETH

FROM HARM AT HOME 1724.

Simple eh? No it's not, the date's wrong! The John Fielden we have been talking about died in 1645. This must be a later descendant, and referring to Fishwick's genealogy of the Fieldens only brings more confusion. Our "John ffeilden of Hartley Royd, Yeoman" had a son called John who "inherited his father's lands with the remainder to his son John" (my italics). This second John would have been at least 79 years old in 1724 so it seems likely that it was a third John, the grandson, who carved the datestone and presumably built the present house. I say 'confusing' because the same genealogy also speaks of another "John ffeilden of Hartley Royd", son of Abraham and Elizabeth Fielden. He is named in Elizabeth Fielden's will in 1673, and in accordance with his father's will conveyed Bottomley to his brother Joshua. Has will is dated 14th February 1679!

One possible way of easing this sort of confusion is to realise that these wills are referring to land parcels and not to particular residences. The first John Fielden was "of Hartley Royd", yet he owned "further Shore" and part of Mercerfield. To farm it you did not necessarily have to live on it, and the Fieldens owned patches of land all over the place, houses being divided up amongst relatives, and new pastures being acquired by marriage. Eventually we reach a point where we have to speculate: the John Fielden who was Abraham's eldest son had two sons who inherited lands, Joshua of Swineshead and Nicholas of Shore. Neither of these could have been "from harm at home" at Hartley Royd in 1724, so I am led to conclude that it must have been the third John mentioned earlier who raised the datestone.

Looking at Hartley Royd raises more speculations. If this house was indeed built in 1724, what of the earlier house? The style of the present building with its mullioned windows and externally protruding chimneybreast is more evocative of the 17th than the 18th century. This fact leads us to two possible conclusions. Either the house was built in 1724 in a style which by that time was going out of fashion (this is by no means unlikely as Pennine hill farms were

Hartley Royd from Hudson Bridge.

severely functional in design and styles were a lot slower to change than they were in more 'civilised' areas), or the house was built in the 17th century and underwent alterations in 1724 which resulted in the datestone we now see. And a final question: irrespective of when the present house was built, was there an earlier, perhaps Tudor, house on them site? Or an even older one perhaps? We do not know, we can only speculate.

In 1648 George Fox began public work in Manchester, and William Dewsbury probably preached around Todmorden in 1653. In 1654 John Fielden of Inchfield and Joshua Fielden of Bottomley were reported as being Quakers. By association with his brother Joshua, it is apparent that this John Fielden is the same one who is referred to in th genealogy as being "of Hartley Royd" who "conveyed Bottomley to his brother Joshua". If he lived at Inchfield, his father Abraham did, and John was his eldest son, that should clarify further the mystery of who lived at Hartley Royd.

John suffered for his Quaker faith: in 1665 he was fined for not attending church and as he declined to pay, a cheese was taken off him and sold for 4s. 6d. Three years later he suffered 31 weeks imprisonment for non attendance, whilst the following year five of his oxen were seized and sold (at a value of 23 pounds) and he himself spent eight weeks in jail at Preston. His brother Joshua was buried at Shoebroad on his death in 1693.

John died in 1698, but there is no mention of his resting place. There is another Quaker burial ground at Todmorden Edge, and Mrs King informed me that at Shore there is a field called "t'Quaker Pasture." Quakers were not allowed any monuments or gravestones, so their burial grounds are not immediately apparent. Perhaps somewhere in the "Quaker Pasture" at Shore lie the mortal remains of "John ffeilden of Inchfield and Hartley Royd, Yeoman."

Before visiting Todmorden Edge, and another chapter in the Fielden story, we visit Mercerfield and reflect awhile. From Hartley Royd follow the track that leads through the farmyard towards the valley.

Just beyond the farm buildings another more recent track leads down to a TV booster mast

(leastways that's what I think it is). Just beyond is an iron field gate in a wall. Do not pass

through it, instead hollow the wall to the right. The wall soon becomes a fence running

even more sharply to the right, and Shore Baptist Chapel can be seen on hillside

opposite. At the bottom of the slope a stile enters a dilapidated track coming down from Ridge Gate. Turn left, and

pass through an old gate to the barn at:-

Mercerfield

Only the barn remains, and a rusty old fence straddles the ruins of what once was the house. There is an old door lintel here but the inscription is quite illegible, being badly eroded. The nearest I could get was:

HE C . . . 17 . . .

On the other side of the fence is a more legible stone with the date 1829. Mercerfield was divided between Nicholas and Christobel Fielden's sons John and Anthonie. It seems unlikely that there was a house here in the early 17th century, but there is no way we can be sure. If there was a house here in those far-off days, it must have been a tiny one judging by the ruins of the more recent house.

Here at Mercerfield, tucked snugly on its hillside in a hollow beneath the TV mast, with fine views down the gorge to Cornholme and its mills, is a place to sit down, break out the coffee and let your thoughts wander. Hartley Royd was a fine house, but it was also a farmyard, alive and kicking, fraught with canine menace and bovine sanctity, hardly conducive to flights of fantasy. Here, sitting amongst the pathetic ruins of Mercerfield we are alone with the hills, and we can, beset on all sides with Johns and Joshuas, try to find some clarity in the murky confusion. We can travel in time and try to get a picture of what life must have been like for those yeomen farmers and their families.

What a different world it must have been for those early Fieldens. Nicholas Fielden's grandfather was alive in the reign of Henry VIII. He would have lived through the dissolution of the monasteries, the Pilgrimage of Grace, and would have witnessed some of the repercussions of these events. Life must have been harsh, austere and uncomfortable in those turbulent times. Houses were cold and draughty, and lighting poor or non-existent. The noble 17th century farmsteads and clothier's houses we see on the hillsides today belong to a later generation of housing, born of a minor revolution in techniques of quarrying and stoneworking. Tudor houses in the Pennines were timber framed, often with walls of lath, wattle and daub rather than stone, and smokeholes in the roof rather than sophisticated flues and chimney stacks. Cruck houses, built with skills and techniques passed down from Norse settlers, were common, so backward was this remote upland area. Earthen floors and log fires —these are the kind of houses the Fieldens' mediaeval forebears would have known. The only towns of any note were York, Lancaster and London, and they were far away, almost in another world.

Nicholas Fielden's grandchildren would not have found life too comfortable either. Their homes, though more embattled and sturdy, could have been every bit as uncomfortable. They would keep

livestock on these bleak pastures and supplement a meagre living by producing woollen cloth to be sold at the nearest market, probably Heptonstall. Later, merchants and middlemen would become involved and

the domestic textile industry developed, but at this early stage it would have been every man working for himself.

John and Joshua Fielden, Nicholas' grandchildren, were persecuted for their nonconformist beliefs. They lived through the great Civil War, and were no doubt aware of, if not actually involved with the skirmish "ovver t'hill" at Heptonstall between the Parliamentarian garrison there and Mackworth's Royalists, who marched out of Halifax only to be repulsed by crashing boulders and fast flowing waters. They might also have witnessed the garrison's departure over the moors into Lancashire (perhaps along the very packhorse route that runs above Hartley Royd) and heard reports of the sacking and burning of Heptonstall by the Royalists. Perhaps,

with their Puritan beliefs, they wondered if their familes might next be

ravaged and put to the sword? As Quakers their sympathies would have no doubt lain with the Parliamentary cause, even if their faith forbade them to take up arms.

The only thing we do know is that they survived these turbulent times, probably by minding their own business. Poor hillfarmers like the Fieldens would have little to offer the foraging armies of the Civil Wars. Indeed then, as now, the whole area would have been hostile to people in search of shelter and wholesome food. Good food came from the rich farming areas of the lowlands; the high hills and moors of the Pennines were only good for sheep farming and rough pastures. In the war, food supplies from the arable lowlands would have been cut to virtually a trickle, forcing up prices and bringing privation and hunger to the hillfolk of the Pennines, who eked out a living by selling their cloth. Times must have been hard indeed.

However, the sound of a train coming up the valley towards Cornholme breaks our reverie and we are back to the present day.

Other Fieldens and other centuries await us, so we must say goodbye to

the Fieldens of Shore, and push on up the other side of the valley towards Todmorden Edge. As you descend towards the bottom of the valley, make a good note of the topography of the opposite hillside if you intend continuing beyond Section 1. The path, zigzagging up the hillside opposite to a ruined farm on the edge of the moor, is the way out from the gorge and the first part of Section 2 of the Fielden Trail.

From Mercerfield the route is indistinct and there is a multiplicity of sheep paths. The object is to get down to New Ley, a tiny little farmhouse in a ruinous condition, surrounded by nettles. The roof is starting to collapse now, but its size and interior give a pretty good idea of what Mercerfield must have been like when it was standing. For that reason alone, it is worth stopping for a moment.

From New Ley an enclosed path leads down to another ruined farm with green painted lintels, where it joins a track coming in from the left. The track descends towards a bungalow near some red brick honuses, to emerge into Frieldhurst Road. Turn left and pass under the railways line to emerge into the main Burnley Road.

This is the end of Section 1. If you are not continuing onto Section 2

this is the place to catch a bus back to Todmorden. On foot it is a long walk down a busy road,

but if the hour is late, this is preferable to following Section 2, which involves some

awkward countryside and a lot of ascent, not very enjoyable in bad weather. I'd catch the

bus if I was you, you can always tackle Section 2 on another day when you feel up to it. Don't

worry about it, we'll go on our own!

Copyright Jim Jarratt.

2006 First Published by Smith Settle 1989

This was the first Board School in Todmorden, opened in 1878. (The remains of the playground walls can still be seen around the flats.) The Fielden Trail does not visit Roomfield House (there is nothing to see) but instead crosses the little footbridge over the river behind the Market Hall. Pause on the bridge a moment and listen to the following harrowing tale from the statement of Henrietta Shepherd to her son Levi, concerning the brave deed for which her husband James Shepherd was awarded a testimonial and a silver medal from the Royal Humane Society:

"On the 14th August 1891 there was a terrible flood. The River Calder was in full spate, and [downstream of Todmorden] was running level with the canal, forming huge lakes across the valley. Here, at Roomfield, the school was flooded and children had to be rescued from the school. To do this, long planks were put across weft boxes to form a bridge, for the children to cross over. Whilst the children were walking on these planks, one little boy, Samuel S. Fielden, fell into the roaring river and was quickly washed out of sight.

At Springside [about 21/2 miles downstream] people had been alerted about the accident, and were watching the river for a sight of the boy. One of these people, James Shepherd, Foreman Dyer at Moss Bros. Springside, saw the boy in the river and immediately jumped into the river, and reached the boy. Being a powerful swimmer, he managed to get the boy to the side of the river near Callis. Here help was at hand to pull them out. The boy was badly bruised by his rough journey down the river, and only survived a few hours. James Shepherd was none the worse for his ordeal. The courage of this man must be appreciated, when you realise that he had a wife and seven children at home. The youngest, twins, were just two months old.

Later James Shepherd was presented with his testimonial and silver medal. On the face of the medal is engraved:

'Presented to Mr. James Shepherd.'

On the reverse:- 'For saving Samuel S. Fielden from the River Calder, 14th August 1891. Presented with a testimonial from the Royal Humane Society for his bravery.'

The Fielden family also presented him with a new suit of clothes for the one ruined in the river. In one of the pockets was a gold sovereign."

So, as you stare at this babbling little brook and try to envisage what kind of a flood it must have been that could sweep a little boy to his death, cross the footbridge (it has steel rails in a trellis pattern, and crosses the river behind the Market Hall, just below the meeting of the Calder with its Walsden tributary), pass behind the Bus Station, (the river flows between concrete walls here and the buses turn on the far side), and go under the railway viaduct, which carries the railway at a high level over the rooftops of Todmorden. Todmorden Viaduct carries the Manchester line over nine arches, seven of them with a sixty foot span, 541/2 feet above the road. The railway was opened on March 1st 1841, and Thomas Fielden, who was one of the railway company directors, proved to be a thorn in the flesh of the board's chairman on more than one occasion, as we shall see.

Beyond the viaduct, cross waste ground by a garage to emerge by a fish and chip shop. Here turn right down Stansfield Road. High on the hillside to the right can be seen the tower of Cross Stone Church, which has Bronte associations. It was originally built centuries ago to cater for the needs of upland farmers, being rebuilt in 1714, pulled down, and re-erected in 1835. It is presently in a ruinous condition. The Bronte sisters stayed at Cross Stone Vicarage in September 1829.

Now continue onwards, bearing gradually to the left. Soon Stansfield Road joins Wellington Road, coming up from the left. Turn right and pass across a footbridge over the railway, passing a YEB installation on the left to emerge on Stansfield Hall Road near its junction with Woodlands Avenue. Bear right and soon a small road appears on the left, by a ginnel with steps, signed 'To The Hollins', close by the entrance gates to:-

Stansfield Hall

'For saving Samuel S. Fielden from the River Calder, 14th August 1891. Presented with a testimonial from the Royal Humane Society for his bravery.'

The Fielden family also presented him with a new suit of clothes for the one ruined in the river. In one of the pockets was a gold sovereign."

So, as you stare at this babbling little brook and try to envisage what kind of a flood it must have been that could sweep a little boy to his death, cross the footbridge (it has steel rails in a trellis pattern, and crosses the river behind the Market Hall, just below the meeting of the Calder with its Walsden tributary), pass behind the Bus Station, (the river flows between concrete walls here and the buses turn on the far side), and go under the railway viaduct, which carries the railway at a high level over the rooftops of Todmorden. Todmorden Viaduct carries the Manchester line over nine arches, seven of them with a sixty foot span, 541/2 feet above the road. The railway was opened on March 1st 1841, and Thomas Fielden, who was one of the railway company directors, proved to be a thorn in the flesh of the board's chairman on more than one occasion, as we shall see.

Beyond the viaduct, cross waste ground by a garage to emerge by a fish and chip shop. Here turn right down Stansfield Road. High on the hillside to the right can be seen the tower of Cross Stone Church, which has Bronte associations. It was originally built centuries ago to cater for the needs of upland farmers, being rebuilt in 1714, pulled down, and re-erected in 1835. It is presently in a ruinous condition. The Bronte sisters stayed at Cross Stone Vicarage in September 1829.

Now continue onwards, bearing gradually to the left. Soon Stansfield Road joins Wellington Road, coming up from the left. Turn right and pass across a footbridge over the railway, passing a YEB installation on the left to emerge on Stansfield Hall Road near its junction with Woodlands Avenue. Bear right and soon a small road appears on the left, by a ginnel with steps, signed 'To The Hollins', close by the entrance gates to:-

Stansfield Hall

Here time has stood still. The prehistoric worshippers, the legions of Rome, they all departed long ago. In their wake came English, Norsemen and Danes, the first hill farmers, clearing the land, claiming rough pastures from the inhospitable hills, felling the ancient birch forests, digging peat, building farmsteads and laithes, keeping livestock, and, perhaps most significantly of all, carding, spinning and weaving woollen cloth. No doubt there were ancestors of the Fieldens among these people, not to mention the Stansfields, Greenwoods, Radcliffes and various other ancient families indigenous to the Upper Calder Valley.

In the wake of the farmers (and in some cases before them) came the arteries of communication, the drove roads and packhorse ways; and, walking on the old causey stones below the Bridestones and Whirlaw, we might, in this quiet solitude, almost hear the jingle of packhorse bells. 'Long Causeways', ancient boundary stones and wayside crosses all abound in this area. Are they Tudor, Mediaeval, or Viking? Perhaps even older? No one knows. English history went its schoolbook way: red rose fought white, the monasteries were dissolved, first the Renaissance and then the Reformation swept Europe; yet right here, in these bleak northern uplands, we might still be in ancient times, such is the scarcity of information relating to this area as it was in those far off days.

High above the valley floor on this upland shelf, what civilisation there was in the Upper Calder Valley first developed. (The valleys were marshy and thickly wooded.) From this level, with the advent of the Industrial Revolution in the late 18th century, the pattern of development was to move downhill, building factories and towns, leaving solitude and desolation in its wake as the surge towards progress, industry and improved communications led embryonic industrialists like the Fieldens to abandon the stony places of their youth, and become dwellers in, and builders of, large industrial townships like Todmorden. Up here, in the shadow of rock outcrops and moors, is where the Fieldens (and many families like them) began, eking out a harsh living from bleak upland pastures. Down in the valley is where they went to make their fortunes, and back to the countryside (in gentler climes) is where they returned afterwards to build their great houses, returning not as poor yeoman farmers, but as influential landowners, weighted with honours and privileges.

Walking amongst rough hewn ruins on bleak hillsides we are now at the beginning of our trail of inheritance. Through these upland Pastures (and very likely along this ancient packhorse way) sometime in the middle of the 16th century came Nicholas Fielden, yeoman farmer of Inchfield in the Parish of Rochdale. His father, William Fielden, was also a farmer, though his roots are rather less clear, it heing uncertain as to whether he came from Leventhorpe near Bradford, or Heyhouses near Sabden.

Whatever his roots, however, the business that brought Nicholas Fielden so far from his own home in the adjacent Walsden Valley to these bleak Whirlaw uplands is quite clear: he came as a suitor. On this side of the Calder Valley dwelt Christobel, daughter of John Stansfield of Stansfield, and Nicholas eventually married her. Whether or not Nicholas and Christobel walked hand in hand along these hillsides, the wind in their hair, or were merely the unwilling victims of their parents' dynastic ambitions, we can only speculate. One thing we do know is that their marriage, arranged or not, was fruitful, and we must Hope that they were happy together.

As a result of this union, the farms of Hartley Royd and Mercerfield (which we are shortly to visit) passed to Nicholas' children, of which he had five (four sons and a daughter), before Christobel died sometime after 1582. Nicholas remarried, taking as his second wife Elizabeth Greenwood, who, in 1638 was described as 'living at Inchfield aged' (Nicholas having died in 1626). Whether or not Nicholas' children acquired these Calderdale estates as a result of their mother's inheritance or marriage settlement is uncertain, but it seems likely, as there would appear to be no record of any Fieldens living on this side of the valley prior to this period, which suggests that the lands originally belonged to the Stansfields.

Unfortunately the picture of the Fieldens in the 16th and early 17th centuries is not as straightforward as this. The Fieldens of Inchfield (and later Shore, Hartley Royd and Mercerfield) were not the only family of that name living in the vicinity of what was eventually to become Todmorden. On the opposite side of the Walsden Valley to Inchfield, at Bottomley, another family of Fieldens was firmly cstablished. Whether or not they were cousins to Nicholas' family is not clear. One thing is certain however: in the near future a Fielden was going to marry another Fielden and from this union was to spring that branch of the Fielden family with which this book is concerned.

From West Whirlaw the causey passes over the moor amongst boulders and heather, beneath Whirlaw and the Bridestones, which dominate the horizon on the right. After a succession of metal gates the path becomes a 'green lane' running between walls. Continue to the next iron gate, just beyond which the Calderdale Way branches off to the left, down to Rake Hey Farm and Todmorden. Ignore this route, instead continuing onwards along Stoney Lane, passing trees and ruined farm buildings (named 'Springs' on the 1844 map). Keep going and soon, after a gentle rise, the lane reaches a junction of paths at Pole Gates.

Here a choice must be made. Do not follow the lane onwards, but pass through the gate to the left. From here an indistinct path bears to the right over Hudson Moor to Hudson Bridge and Hartley Royd. Most walkers, however, will be tempted to follow the farm track down to Orchan Rocks. After all, you will argue, I've talked at length about strange rocks and pagan rituals, but I haven't taken my route to any of them! Well now's your chance: Orchan Rocks are not very far off route, and visiting them is well worth the necessary detour, so, just to make you happy, I'll take my main route that way!

The way is quite obvious. Follow the track downhill and then cut across open moorland until you arrive at the Orchan Rocks. Here is another place to break out the flask and sandwiches. If you can stand the 'airiness' of the situation there are superb views over the gorge below. Many names are carved on the slabs, although I could find no Fieldens among them when I was there. The Fieldens would have known this spot however, and, like us, would no doubt have marvelled at its strangeness.

From Orchan Rocks bear right over Hudson Moor. Soon, near some quarrying remains, a distinct path is met with, and Hartley Royd can be seen on the far side of Hudson Clough. Follow the path to Hudson Bridge, then continue onwards, finally entering the Hartley Royd farm road through an iron gate. Turn left to arrive at....

Hartley Royd

In 1624 Nicholas Fielden of Inchfield (whom we have recently encountered) made out his last will and testament, which divided his property amongst his children. To his eldest son John he bequeathed "ffurther Shore" and a moiety (or part) of Mercerfield. Hartley Royd must have been included in this package, for in his own will John Fielden is described as 'John ffeilden of Hartley Royd, Stansfield in the County of York, Yeoman.' The second son, Abraham, inherited Inchfield, and his eldest son, John, also lived at Hartley Royd. Abraham married Elizabeth Fielden of Bottomley, thus uniting two branches of Fieldens, and it is this line whose fortunes we are to follow throughout most of this book. This Abraham Fielden was 'Honest John' Fielden's great, great, great grandfather.

But back to Hartley Royd. Further Shore passed to Nicholas' third son, Joshua, and the other half of Mercerfield went to the youngest, Anthonie. Confused? You soon will be! How, you will ask, does all this relate to the mullioned farmhouse that stands before us? Did John Fielden build the place? The first thing you will notice is the ornate datestone in the north wall, then you will try to read it, but its very serpentine ornateness makes it difficult to decipher. Oh dear, it's in Latin! At this point I was lucky enough to receive the assistance of Mrs. King, the farmer's wife. She said that people often tried to decipher the inscription, so much so that her son had been prompted to sit down one day and find out what it actually did say. It reads as follows...

JOHN FIELDEN AND WIFE ELIZABETH

FROM HARM AT HOME 1724.

Simple eh? No it's not, the date's wrong! The John Fielden we have been talking about died in 1645. This must be a later descendant, and referring to Fishwick's genealogy of the Fieldens only brings more confusion. Our "John ffeilden of Hartley Royd, Yeoman" had a son called John who "inherited his father's lands with the remainder to his son John" (my italics). This second John would have been at least 79 years old in 1724 so it seems likely that it was a third John, the grandson, who carved the datestone and presumably built the present house. I say 'confusing' because the same genealogy also speaks of another "John ffeilden of Hartley Royd", son of Abraham and Elizabeth Fielden. He is named in Elizabeth Fielden's will in 1673, and in accordance with his father's will conveyed Bottomley to his brother Joshua. Has will is dated 14th February 1679!